In 2024, 233,000 people were killed in wars, a 30 percent increase from 2023. The trend seemed inexorable. Political apathy in the face of relentless human suffering fuelled public disgust with government leaders. But then, on 8 December, came a rare piece of apparently good news. One of the world’s most brutal dictators, Bashar al-Assad of Syria, was overthrown.

Does this outbreak of good news herald the arrival of new opportunities for peace-making, or is it just a pause in the agony? This article looks at the situation in Syria from the perspective of a retired UN official who worked in humanitarian, refugee and peacekeeping operations, as well as on UN humanitarian policy and disarmament. How does this historical moment in the Levant look from this perspective?

Lost Opportunities

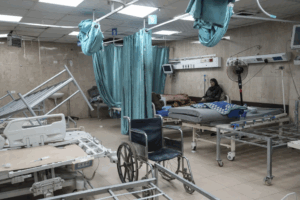

In early 2012, living in the UAE, I made a bet with a colleague that Assad would be gone from Syria by the end of June of that year. On 8 December 2024, nearly 13 years later, it finally did happen. In the meantime, half a million of the Syrian population of less than 30 million people had been killed, nearly 7 million had fled the country, around the same number had been uprooted, many more than once, within Syria, and tens of thousands had been incarcerated, tortured, and killed in the regime’s notorious prisons. A once stable economy was wrecked, and widespread poverty took hold. All this was the consequence of failures of international leadership and many lost opportunities to shorten the conflict.

The Failure of UN Efforts

As I watched Kofi Annan, Lakhdar Brahimi, Staffan de Mistura, and Geir Pedersen struggle in vain to bring Assad and opposition leaders to the negotiating table, it became clear that the lack of pressure on Assad to accept compromise had doomed their efforts.

Human Rights and Justice

Senior diplomats from the US, the UK, France, Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands often voiced support for dislodging Assad and holding him accountable. However, they did not put enough resources or political capital behind efforts to achieve this objective. As one commentator put it, ‘In Syria, billions have been spent on weapons, billions on humanitarian aid, millions on political initiatives, but almost nothing on justice and accountability’. Blessed are the peacemakers, but our governments will spend their money on weapons and humanitarian aid to help those wounded by the weapons.

The Military Industrial Complex and the International Humanitarian System

The military-industrial complex thrives on war, and can always find ambitious leaders to pursue their political ambitions with violence. Humanitarian organizations have always been ready to request more funds for relief. Until now, wealthy governments have preferred to be seen as generous in disbursing aid but have shied away from prioritizing genuine peacemaking efforts and enforcing adherence to the laws of war, enshrined in the Geneva Conventions.

What to Expect in Syria in 2025

Will the international community learn from the failures in Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan? Will refugees be able to return without premature pressure? Will transitional justice be introduced in a region that lacks precedents for such initiatives? A paper from the ICG (International Crisis Group) warns against repeating in Syria the mistakes of Afghanistan, while Khaled Mansour argues for a complete overhaul of the UN’s presence in Syria.

No to Early Elections

Rushing to elections often undermines peace-building efforts. It pushes political leaders to take extreme and polarizing positions to ‘shore up their bases’. Yet Western states and the UN have often insisted on this approach. This obsession must be resisted.

Syrians Are Up for the Challenge

Despite the 13-year delay in Assad’s downfall, I remain optimistic. The people of Syria are ready to take on the challenge. Let’s try not to get in their way.

Conclusion: A New Beginning for Syria

The fall of Assad presents an opportunity for Syria to rebuild on a foundation of justice and accountability. However, the international community must resist the urge to impose rushed solutions, such as premature elections, which could destabilize the fragile recovery process. Instead, efforts should focus on removing sanctions that impede economic recovery and on supporting Syrians in establishing inclusive governance structures that break away from the past cycle of authoritarianism. Given the space, Syrians can re-shape their country’s governance system in ways that escape the constraints of patron-client relationships and offer genuinely equal rights and opportunities to all citizens.

About the author: Martin Barber is an Associate Fellow at Chatham House, a former Director in the UN Department of Peace-keeping Operations and a co-founder of United Against Inhumanity (UAI).

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of United Against Inhumanity (UAI).