UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has recently concluded a visit to Bangladesh, where he expressed great concern about the impact of impending aid cuts on the country’s one million Rohingya refugees, as well as their inability to return to their homes in Myanmar. In these circumstances, there is a need to adopt a sustainable and medium-term approach to the situation, removing the many restrictions currently placed on the lives and livelihoods of the refugees.

Preparing for starvation

In the first week of March 2025, the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP) announced that severe funding shortfalls had forced it to halve the monthly food voucher provided to Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, reducing it from $12.50 to $6 per person.

In a message transmitted to the refugees, WFP stated that “we are sorry to inform you that we do not have enough funds to continue providing the full ration” and that “we are doing everything possible to secure more funding.” In the meantime, it advised the refugees “to make the most of your food voucher by planning and prioritizing well. Stretch your food supply by buying in smaller quantities. Cook efficiently and store food properly.”

Unimpressed by this advice, one young Rohingya refugee woman took to X, commenting, “WFP is informing us to prepare for starvation. ‘Stretch your food’. How do you stretch nothing? We Rohingya have no food. We are losing all hope.”

The immediate cause of the refugees’ distress is to be found in drastic cuts to humanitarian assistance recently made by the US and other major donor states. At the same time, emergencies in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Syria and Ukraine have placed mounting and unsustainable pressures on the international aid system. As WFP explained in its message to Rohingya refugees, “Many of our operations outside of Bangladesh are also facing similar funding shortages.”

A lack of solutions

To understand the origins and depth of the crisis currently confronting the Rohingya refugees, it is necessary to look beyond the issue of the current food aid cuts.

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority group from Myanmar who are not recognized as citizens of that country and who have been subjected to intense persecution since the 1970s. Around a million of them are to be found in Bangladesh, three-quarters of whom arrived after a genocidal military operation against them in 2017.

From the moment of their arrival, the government of Bangladesh, donor states and the United Nations all worked on the assumption that the Rohingya refugees would quickly be able to return to their homeland. But that assumption proved to be wrong. Indeed, conditions for the estimated 500,000 Rohingya remaining in Myanmar deteriorated further following a military coup in 2021, which triggered a nationwide conflict between the new junta and a variety of different ethnic armies.

Since 2017, Bangladesh has made repeated attempts to encourage and induce the return of the Rohingya to Myanmar, but these efforts have come to nothing. And the prospects for their repatriation now seem bleaker than ever. Myanmar’s Rakhine State, the home of the Rohingya, has been convulsed by fighting between junta forces and the Arakan Army, a group that now controls much of the state’s territory and which has itself been accused of persecuting the Rohingya that remain.

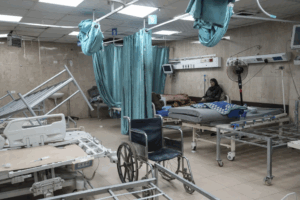

On the Bangladesh side of the border, the recent cuts in food aid have exacerbated what was already a dire situation for the Rohingya. Since the beginning of the emergency in 2017, the Rohingya have been obliged to live in overcrowded camps, with severe restrictions placed on their freedom of movement, access to education and ability to establish livelihoods. As a result, they have become dependent on international aid.

With their numbers growing as a result of births and new arrivals from Myanmar, the refugees have been confronted with a variety of other threats: murders and kidnappings by militant groups; large-scale fires, some of them suspected to be the result of arson; intimidation by Bangladeshi security personnel; and high-levels of criminality, including human trafficking and gender-based violence.

An alternative approach

It has now become apparent that the ‘repatriation or relief’ approach to the plight of the Rohingya in Bangladesh has failed. On one hand, the refugees themselves have made it clear that they want to return to Myanmar, but only if they can enjoy security and citizenship there. Those conditions seem highly unlikely to be fulfilled in the near future.

Armed conflict is still raging in their homeland, and there is no sign that it can be brought to an end by the diplomatic manoeuvres of the UN or the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN). On the ground in Rakhine State, the ascendancy of the Arakan Army and the many doubts that exist with respect to its willingness to respect Rohingya rights appears to preclude the prospect of any early repatriation.

In the absence of returns to Myanmar, Bangladesh has continued to insist on a strictly relief-based approach to the Rohingya situation, believing that the refugees could be encouraged to go home at the earliest possible opportunity by keeping them at the most basic level of existence. In the same vein, the authorities in Dhaka have for many years acted on the assumption that the Rohingya will choose to remain in exile indefinitely if they are allowed to live a less stringent life in Bangladesh.

The time has come for those assumptions to be challenged. While maintaining the ultimate goal of safe and voluntary return to a rights-respecting Myanmar, there is a need to consider the adoption of a sustainable medium-term strategy that would enable the Rohingya to exercise freedom of movement, to enjoy better access to education and training opportunities, and to reduce their dependence on aid by enabling them to engage in economic activities that also bring tangible benefits to the host population.

There are a number of reasons why the time is right for such an initiative. First, Bangladesh has a new government, brought into office by a popular uprising against the former regime in August 2024. While it has not yet proved amenable to the medium-term approach recommended in this article, it has shown a greater degree of empathy for the Rohingya population than its predecessor, and might be incentivized to reconsider its position, especially if an alternative approach could attract substantial investment in the economy and infrastructure of areas populated by the Rohingya.

Second, while those areas have undoubtedly been adversely affected by the presence of so many refugees, their number could be reduced if the Rohingya were allowed to seek opportunities in other parts of the country. Bangladesh is a large state. The refugees constitute less than one per cent of its population as a whole. It has a growing economy and is projected to move out of the Least Developed Country category by the end of the decade. It is in a position to mobilize concessional development financing for areas where Rohingya refugees are living, pending the time when repatriation to Myanmar becomes possible.

Third, later this year, and at the initiative of Bangladesh, an international conference will be held on the future of Rohingya refugees. While the venue, timing, agenda and objectives of the gathering remain to be determined, the conference provides an important opportunity to reconsider their plight and how it might be resolved. Irrespective of where their future lies in the years to come, hope and humanity must be restored to them.

About the author: Dr. Jeff Crisp is a Visiting Fellow at the Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford, former Head of Policy Development and Evaluation at UNHCR, and a volunteer with United Against Inhumanity (UAI).

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of United Against Inhumanity (UAI).